Menthol and media

Today’s newsletter is longer than usual, wading into some very different topics. But first, some recent writing and video appearances…

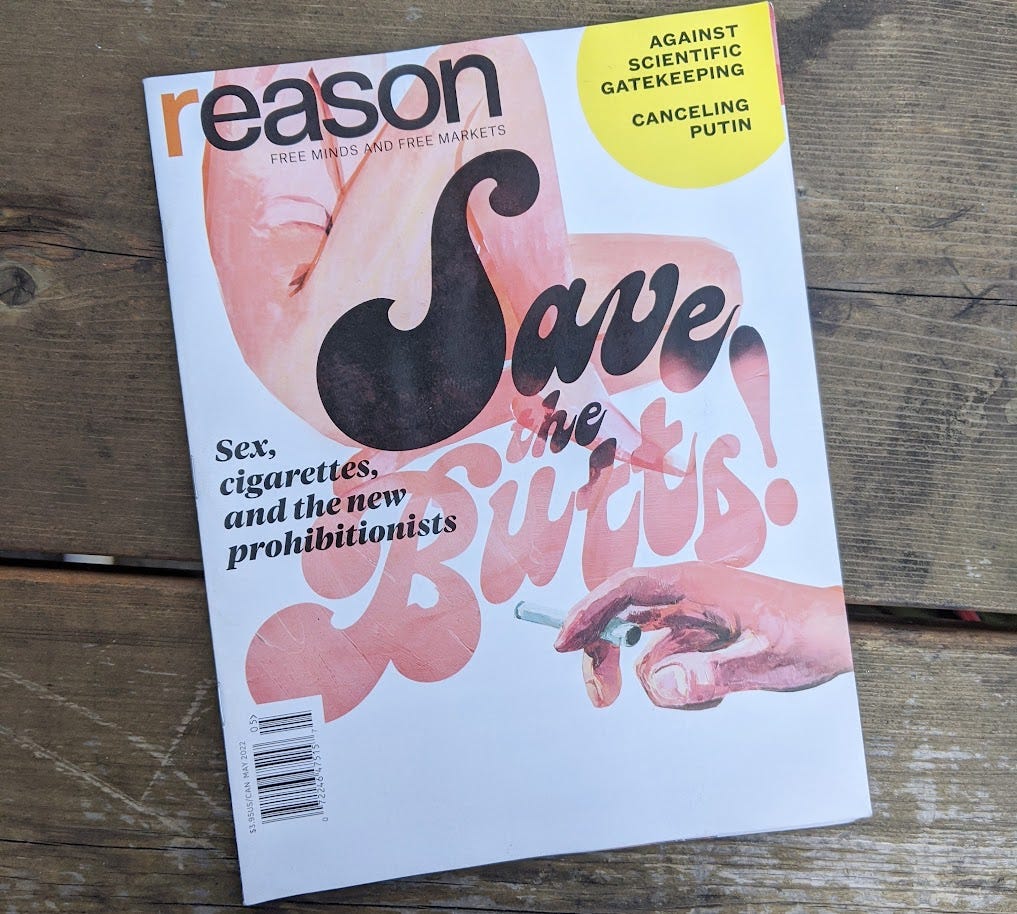

This morning, the Food and Drug Administration announced a federal ban on menthol cigarettes and flavored cigars. Advocates reasonably claim that banning menthols will have benefits for public health. Less discussed is what this will mean for law enforcement and criminal justice. My cover story for Reason dives into how new policies on flavored tobacco and e-cigarettes are ushering in a new era of nicotine prohibition that will lead to illicit markets, police enforcement, and imprisonment for the crime of selling tobacco products to consenting adults. Read it here, now free from behind the paywall.

I also have a piece up on Liberal Currents on how these laws are already leading to arrests and prosecutions at the state level, making flavor bans an emerging issue in criminal justice. I discussed this in a couple of recent videos too with Brent Stafford of Reg Watch and the weekly live show of the Consumer Advocates for Smoke-free Alternatives Association, the latter with my longtime Twitter friend Amelia Howard. Lastly, don’t miss Elizabeth Nolan Brown’s cover story from the same issue on campaigns for a sex-free internet.

Facebook, Twitter, blogs, and Seabird

You’ve surely heard the big news in tech this week: I’m starting a new platform! Oh, and some guy named Elon is buying Twitter.

I guess this technically means that Elon Musk and I (along with two great partners) own competing companies now, which is not a position I expected to be in anytime soon. “Competing” is putting things ridiculously generously. Twitter and Elon Musk have billions of more dollars than I do. (Rounding to the nearest billion, my net worth is zero dollars.) Twitter also has more than 200 million active users; we have a small private beta group of a few dozen.

I’m not going to join the pile-on predicting a failed takeover of Twitter (if it actually happens), although I’m as mystified as anyone how this will turn into a good investment and am not convinced that a dearth of free speech is really one of the top problems plaguing the app. But Musk is also a brilliant entrepreneur who’s successful in businesses that seemed improbable, so I’m curious to see what he does with the platform and am prepared to be surprised.

I’m also not going to go into complete detail yet about the new thing we’re building, but I will write a bit about why we’re working on it, why we think it’s needed, and what I’ve personally been thinking about with regard to how I approach social media. I can tell you that our new platform is called Seabird, that it’s a collaboration among myself and my very smart friends Courtney Knapp and Jay Mutzafi, and that we’ve recently received a grant from the Mercatus Center’s Program on Pluralism and Civil Exchange to develop it. It’s currently in a private beta, but if what I write below intrigues you, you can sign up on the website to be invited to future phases.

Putting politics in its place (not on Facebook)

Sometime in early 2021, I made a conscious decision to completely disengage from political discussion on Facebook. It wasn’t a New Year’s resolution exactly. January of last year was an unusually active month in American politics (to put it mildly!) and I was posting through it as much as anyone. But watching in horror as rioters stormed the Capitol, doubt was already setting in as to whether there was any point to posting about it. Would anything I wrote change anyone’s mind? Or worse, was the temptation to post about politics part of what led to this situation in the first place?

A few months before, I’d read Vanderbilt philosopher Robert Talisse’s recent book Overdoing Democracy, which has greatly influenced the way I think about polarization and social media. Talisse’s thesis in brief is that the saturation of politics into everyday life is corrosive to democracy, contributing to the formation of all-encompassing identities and bitter polarization in beliefs. Everything becomes laden with politics — where we shop, what we drive, what kind of coffee we drink — and we self-sort according to our politics. “In a nutshell,” Talisse writes, “as our political identities have become who we are, politics has become everything that we do.”

This sets off a vicious cycle of belief polarization:

Corroboration from the relevant identity group increases our overall level of commitment to our perspective and prompts us to adopt more extreme beliefs in line with our antecedent identity commitments. From the standpoint of that intensified outlook, opposing views and countervailing considerations are bound to appear distorted, feeble, ill-founded, and extraneous. […] As belief polarization takes effect, we come not only to believe firmly things that are further out of step with our evidence, we thereby also lose sensitivity to the force of reasons that drive the views of our opponents and critics.

Accordingly, once we are sufficiently belief-polarized, those who espouse views that differ from ours will strike us as more and more alien, benighted, incoherent, and perhaps even unintelligible. Thus the intellectual distance separating us from others will seem to expand momentously, and indeed, those who hold views that run directly contrary to our own will strike us as irrational extremists, people devoted to views that make little sense and enjoy no support.

This dynamic is likely familiar to you if you engage with politics at all. Perhaps the description above brings to mind someone whose views you used to think you understood who now seems to have gone off the deep end. And you may be right; many people have in the past few years! But the more challenging point is that this cycle also pushes our own political identities to extremes. We forgive or even embrace the inexcusable excesses of our own side while assuming the worst about those we disagree with, who become more extreme in turn. In other words, “we actually become more like what our most vehement political opponents think of us, and they grow more closely to fit our distorted images of them.”

The standard response to this is to say that we need to meet in the middle, to compromise, to hear each other out, to get out of our echo chambers, to set aside time and space for a real productive dialogue. Democracy is failing? Then we need to do democracy harder!

And yes, we probably could do more of that. But Talisse takes the argument in a different direction, making a compelling case that by overdoing democracy — by making everything political and bringing our political identities into everything — we often end up undermining it. Instead, we should aim to deemphasize politics in our social environments and relate to each other non-politically, at least some of the time:

And so, in addition to unplugging and checking out of the most heavily politically saturated regions of one’s social environment, one should also engage in a certain level of restraint and perhaps refusal. For not only do our social environments contain political messaging and other stimuli, they function so as to extract political behavior from us. To repeat, putting politics in its place does not require political quietism or resignation; it rather involves the insistence that not every aspect of our lives that could be a site for democratic citizenship therefore must be put to that use, and the corresponding resolve to resist the perpetual instigations to commit overt acts of political communication. In other words, putting [politics] in its place involves establishing boundaries within our social environments, and thereby restricting the reach of democracy so that social encounters of other kinds can take place. Hence it is consistent with being a vigilant and conscientious democratic citizen who is fully devoted to justice to simply refuse to use Facebook as a site for political action, for example. And although friends and feeds might contend otherwise, there is no dereliction of one’s political duty in using social media strictly to look at videos of pets.

This is a counterintuitive suggestion. The idea is not that we should seek to manage polarization by seeking out dialogue with our opponents (though we should do that too), but rather to seek out relations that have nothing to do with politics, where we don’t even know what other peoples’ politics are. The intensification of political life means that we tend to be constantly relating to and evaluating each other in our roles as participants in politics, with these identities creeping into our relationships as neighbors, coworkers, teammates, friends, and family and contributing to negative affect toward each other when our identities clash.

Breaking this cycle is harder than it sounds. For one, our physical spaces are increasingly sorted. If I hang out in an indie coffee shop in Portland, for example, I’m unlikely to meet many conservative friends, regardless of whether the subject of politics comes up. Online spaces are even worse. If you’d set out to design a machine to create political mega-identities, it would look a lot like Facebook. The timeline invites users to take all their roles and hobbies — their family photos, vacation stories, job announcements, photos of their pets and cooking — and mix them up with political news and memes. Maybe you become Facebook friends with someone you met at church or the soccer field, knowing nothing of their politics. Before long, you’ll know to your delight or regret if you share each other’s views, and your attitudes toward each other will shift accordingly.

The cycle is also hard to break because we’re only human. We like expressing our political identities, whether to win praise from our allies or to tweak the noses of our opponents. And the more things get sorted and coded politically, the more opportunities there are to do this. Take the chants of “Let’s go Brandon” at football games. (For those not in the know, this is code for “F— Joe Biden.”) It’s not just that this is juvenile and vulgar, although it is that. It’s also failing at being a sports fan. If you’re spending your time at a football game thinking about the president of the United States and how to own the libs, you’re doing football wrong. You’ve lost the ability to relate to sports as just a fan, and it’s kind of pathetic.

Once you’ve been Talisse-pilled (a term I suspect he’d resist), you start to see this unnecessary saturation of politics into non-political roles everywhere. On the left, maybe it’s kicking off a corporate HR meeting with a land acknowledgement. On the right, maybe it’s insisting on treating Covid with ivermectin. Whatever the merits of the underlying arguments, they bring political identity into relationships and situations where it’s likely better set aside.

To bring this back to social media, this is one reason I used to appreciate Instagram as a refuge from the politicization of Facebook and Twitter. Whereas those platforms were often dominated by political arguments, Instagram was an oasis of pretty photos of the non-political things users cared about. The shift from static photos to stories, coupled with a rise in activism, changed all that. Now Instagram is equally saturated with politics in an even worse format, in stories that flash on the screen for a few seconds before moving on to the next. It’s the most superficial form of engagement; until recently you couldn’t add a link to follow, and there’s no good way to fact check or dive deeper on a topic. No one is going to click that link between photos of pets and sunsets anyway. It’s a medium for signaling or calling attention to issues, but it’s terrible for persuasion.

For Facebook and Instagram, this is probably all to their benefit. It drives engagement, so they’re not likely to fix it. There’s only so much you can do as an individual too, plus maybe you think that every post you make — because your views are correct and virtuous, of course — makes the discourse a little bit better, your friends and followers a little bit more informed. But if the spillover effects of political saturation really are the problem, maybe there’s something better you can do: unilateral disarmament and refusal to engage.

If you are a Very Online person, it’s famously hard to resist responding when someone is wrong on the internet. But it’s been my policy on Facebook to do so for over a year now, and I recommend it. You don’t have to share that big article in the Atlantic; you don’t have to argue when your friend posts something wildly misinformed. You can shake your head, think to yourself, “how sad for them,” and move on. Unfriend that person if you really have to. It’s fine! It gets easier over time. And maybe it will help build up norms against the political saturation of social media, which would be a positive spillover.

To be clear, this doesn’t mean you have to become apolitical. It doesn’t mean you have to moderate your views at all. It doesn’t mean you have to actively hide them, either. And I’ll acknowledge that as a straight white guy this is all very easy for me to say; the most oppression I’ve experienced recently is having to wear a mask at work for a bit longer than I think was really necessary, so I have it pretty good all things considered. Others may feel the need to call attention to their causes more urgently. Don’t take my personal approach to social media to be meant as universally prescriptive. But I do think there’s a lot to be said for “putting politics in its place,” taking up the challenge of resisting the urge to use every opportunity as an avenue for political expression, and relating to people in completely non-political roles to break the cycle of belief polarization and negative affect toward the other side.

The special case of Twitter

Desaturating politics from most social media platforms is relatively straightforward because the different apps have identifiable purposes outside of political expression. Facebook is for keeping up with friends and family; Instagram is for showing off your aspirational life; LinkedIn is for your professional self; Hinge is for pitching yourself as a potential date. What is Twitter for? That’s a lot harder to answer.

When Twitter launched it was inscrutable. All you could do was post a sentence or two of text at a time. It wasn’t obvious what you were supposed to do with it and a lot of the content was banal stuff like what you had for lunch. This wasn’t a bad thing though; the weird text-based format attracted a lot of smart people to the app. It was a way to stay in touch, to follow the writing of bloggers and journalists, and to jointly experience and comment on live events. And it was an app where people could be very funny.

It still is all of those things. I find more interesting things to read on Twitter than anywhere else and it’s where I most successfully promote my own work. I doubt I’d still be in touch with many of my friends from DC if not for Twitter, and I’ve met lots of other great people through the site. There’s nothing else like it for following a shared event, getting breaking news, hearing points of view that have a harder time breaking through to traditional media, or finding a random expert on some niche topic from across the world. And it’s still very, very funny. Your experience on Twitter depends a lot on how well you cultivate the list of people you follow, but if you do it right it can be tremendously useful and enjoyable. Twitter is hands-down my favorite social network.

And yet, it’s notoriously toxic. If you talk to journalists, it’s not uncommon to hear that they hate the site but feel like they have to be on it to do their jobs. Even those of us who like Twitter affectionately call it a “hellsite.” It’s a place where a successful writer can reach hundreds of thousands of people and they can reach right back. It’s a technology for getting piled on by angry randos or for losing your job with a poorly thought out joke. It’s tailor-made for polarization. As a poster you might get captured by an audience that drives you to absurd extremes; as a follower, you might get drawn into self-reinforcing communities believing the dumbest, craziest stuff. Getting into Twitter is a bit like reading Ayn Rand as a teenager. It might start you down a path of intellectual betterment, but it might also make you a monster.

Musk’s presumptive purchase of Twitter has gotten a lot of people talking about what’s wrong with the app and how to fix it. If you’re on the left, you probably worry about misinformation and abusive trolls. If you’re on the right, you’re probably focused on censorship and cancel culture. These are valid concerns, but I’m doubtful that there’s any way to really fix them without addressing the more fundamental problem of polarization and political mega-identities. And since Twitter has become the place to go for unrestrained fights about politics, with instantaneous scoring via likes, retweets, replies, and dunks, that’s not likely to happen.

There are lots of steps Twitter could take to become a more pleasant social network. Killing (or giving users the option to turn off) the quote-tweet, which has become a vehicle for viral dunking, would be a start. It could give users more power to control and moderate who interacts with their tweets. It could return to a chronological timeline by default instead of forcing users into an algorithm that elevates divisive content. If you want to imagine far out possibilities, it could get rid of images and go back to being a text-only medium, bringing back a bit of the old inscrutability. The problem is most of these fixes would also limit engagement on the app and drive some users away. And it’s not obvious that Elon Musk, who seems bent on reforming the app around a nebulous conception of free speech, is going to introduce fixes that limit interaction.

So, as much as I love Twitter, I’m not convinced there’s any way to make it more than marginally better while still keeping what makes Twitter Twitter. We expect too many different things from the site. We want it to be the fun virtual place to watch the Super Bowl, follow breaking news, find smart things to read, learn from experts, keep up with friends, make jokes about the new three-hour Batman movie, look at funny cat memes, share our Wordle scores, go viral, open our thoughts up to comment from millions of strangers, and gather for ritual combat over politics all at the same time while somehow not having the site devolve into Boschian chaos. Maybe that’s just not possible. But if we can’t fix it, we can exit and look elsewhere, at least for some of these purposes.

The golden age of blogging

Like a lot of people who have been at this writing online thing for a long time, I’m nostalgic for what we look back on as the golden age of blogging. I’m not going to rehash what was good and bad about it or why it ended. It definitely had its problems, and bloggers could be mean and snarky and polarizing, but in a lot of ways it was much better than the contemporary toxic culture that pervades social media.

One obvious difference between then and now was that blogging was decentralized. A lot of people were on the Blogger service, but you could also host your own site with software like Movable Type or Wordpress. There was never any guarantee that people would read or care about what you wrote, but you were free to write it. As Mike Masnick of TechDirt observed recently, “Twitter is not the town square, and it’s a ridiculous analogy. The internet itself is the town square. Twitter is just one private shop in that town square with its own rules.” If you think Twitter’s rules are too oppressive, one solution is to go back to blogging.

We’re already seeing some movement this direction with the rise of newsletters. Substack, Ghost, and other platforms offer a lot of the same advantages of the old blogosphere, now with the possibility of making money from subscribers, too. One thing these newsletters don’t have quite as much of yet is the culture of ongoing debates and linking back to each other that used to occur on blogs, or a popular discovery mechanism like Google Reader that made it easy to follow writers you like. Substack has introduced a few features to aid with this, but newsletters without big readerships are still dependent on social media to find an audience. (If this post is read by a lot of people, for example, it won’t be because of my small subscriber base. It will be because it gets shared on Facebook and Twitter by people with lots of followers there.)

Another difference between RSS readers and Twitter is that while they can both be used to follow writers and websites, the former doesn’t act as a public discussion forum. You might find a blog post via RSS, but if you want to respond to it you’d have to go that blog’s comment section (if it has one) or write a blog post of your own. Twitter puts both discovery and debate on one central platform. Discussion that previously would have happened on blogs now takes place on social media instead.

This is good in some ways, like giving many more people a chance to be heard, but it has obvious downsides too, contributing to Twitter’s reputation as a hellsite. Twitter makes posting virtually costless for the kind of people Noah Smith dubs the Shouting Class:

Everyone has problems with something in society. And everyone sometimes complains about those problems, which Albert Hirschman called "voice". But for many people, voice is contingent - as soon as the problems are satisfactorily resolved they stop complaining and go back to living their daily lives. But a subset of people will never stop complaining. When a problem becomes less severe, they switch to a different problem. And they will always find some problem that they feel requires their vocal complaint. That subset - the people who will never stop complaining and giving negative feedback - are the Shouting Class.

Blogging is less empowering for this kind of internet person. Anyone can start a blog and writing a post is easy, but it’s not as effortless as posting a tweet. That slight difference in effort has a potentially big impact on what people respond to. Before Twitter, if you came across a dumb blog post, you’d probably just ignore it. If it rose to the level of demanding a response, you’d write a post of your own, and that took some work. On Twitter, you might instead respond to a post with a dismissive gif or brutal dunk, amplifying the worthless content that in the past you would have skipped over. You might even become a bit of a jerk yourself; the rewards of tweeting don’t reliably call forth our best selves.

Ryan Avent wrote a great thread about this dynamic a couple years ago that I think about often. An excerpt:

Blogging was an extremely democratic, low-barrier-to-entry medium. Anyone could set up a blog at one of a number of free blogging sites. But sending a new post into the ether was just that bit more costly than firing off a tweet.

Blog posts could of course blow up. But the potential for instant mass virality was smaller, because drawing attention to blog posts meant creating a post of one’s own, and even link roundups took a bit of effort.

As snarky as blogging could be, the medium generally demanded a minimal level of argument and contextualization greater than what’s asked of twitter users: if, at least, one wanted to attract others’ time and attention.

People will RT some tossed-off nonsense in a heartbeat, if only in order to add their own, equally irritating one-line takedown on top of it. Generally speaking, if you wanted people to engage with your blogpost, you had to do better than that.

As we worry about the dominance of individual social-media platforms, and the editorial power that dominance gives them, the distributed nature of blogging recommends itself. […] Social media is bad in a way blogging never was. It’s sufficiently bad that users and platform operators recognize that it needs to change.

Ryan uses the metaphor of “throwing sand in the gears” to improve social media by dampening the potential for instant virality. That’s one possibility. Joanne McNeil posted yesterday about some others, like building more decentralized online communities or a better RSS reader. A lot of us are on Twitter because of the network effects but nothing about it is inevitable. As Joanne notes:

Twitter could soon become internet history itself. Those who have been online for a while will remember the declines of social media companies like MySpace (once the most popular website in the world), Livejournal, Snapchat, and Tumblr. It can happen gradually: several hours on a platform a day turns to several hours a week, and then finally, you just sort of forget about it. There is never a shortage of things to look at on the internet.

[…]

Whatever should come of Twitter’s deal with Elon Musk, the news is an occasion for all Twitter users to reassess their engagement with the platform. We can’t revive what the blogosphere was in the aughts but we can look at it as model of what communities online still have the potential to be.

I’m not going to pretend I have the answers to all of this, but if you’ve read through this entire post, you’ll have some idea of what I’ve been thinking about while collaborating on Seabird. We’re aiming to create a better online community, one that doesn’t try to do everything and that’s less frenetic, shouty, and polarizing than the sites and apps we’ve complacently accepted. We have a long way to go before we completely open it up, but it’s high time to try new things and I’m excited about the possibilities.

Dealer’s choices

To read: On the subject of being too online, this is apt opportunity to recommend Patricia Lockwood’s novel No One Is Talking This, which veers from he strangeness of life in the portal (our screens) to the illuminating intrusion of tragedy in real life. “A person might join a site to look at pictures of her nephew and five years later believe in a flat earth,” is one on-theme line from the book. If you’re online enough to know what an allusion to someone not being sad about an alligator eating a kid refers to, this book is for you.

To listen: Sometimes algorithms are good. Spotify, for example, has my appreciation of bad ass woman songwriters locked down. Lady Lamb is an artist I probably wouldn’t know if not for Spotify. I’ve been listening to her for about a year now, and when she came up in an automated playlist weekend I decided to see if she was playing Portland anytime soon. It was ideal timing; she was playing that night. Closing with the visceral “Crane Your Neck,” it was one of the best live performances I’ve seen all year. Check out her album Ripely Pine.

To watch: That Batman movie really was too long though, right? I am very much the target market for a three-hour Batman movie, and I liked it well enough, but if I don’t spend another minute in that particular Gotham, that will be fine with me. You can add me to the list of fans of Everything Everywhere All at Once though: brilliant, funny, tender, incredibly imaginative and weird, blending wild action with a humane approach to accepting a bounded life in an infinite universe. I loved it.

To drink: I like to think I’ve shown admirable restraint with the relatively scant number of aquavit cocktails I’ve included in the newsletter, but today we’re going in on one. It’s also one that uses an aquavit you’ll have to search for. But fear not! If you can’t make the drink as described, I have a simpler alternative for you too.

To make this drink you’ll have to track down a bottle of Brennivin Rugbraud. Brennivin is the iconic liquor of Iceland, an aquavit flavored with a potent dose of caraway. Rugbraud (or rúgbrauð) is a delicious, dense Icelandic rye bread traditionally cooked in underground thermal energy ovens. To make Brennivin Rugbraud, they take the bread and infuse it into the aquavit. It comes out looking like a barrel-aged spirit, but all the color comes from the bread. The combination is fantastic. Caraway and rye — who knew? (Here’s a video about the bread, including a recipe for making it at home. I want to try it soon.)

For the winter menu at the Multnomah Whiskey Library, I thought it would be fun to make an Old Fashioned-style cocktail with this and a few other breakfasty flavors. We have rye bread for the toast, so maybe some apricot for the jam? Maybe an apple too? And what’s breakfast without coffee? It all came together in the Breakfast in Reykjavik:

1 oz Brennivin Rugbraud

1 oz Old Delicious apple brandy

1/2 oz Bailoni apricot liqueur

1/4 oz Caffe Corretto coffee liqueur

lemon peel

Stir everything, including the lemon peel, then strain into a glass with ice, preferably a big cube. (I included specific brand recommendations here because some of these ingredients are fairly distinct. Feel free to make substitutions, but your mileage may vary if you do.)

OK, but what if you don’t have all that? Here’s a simpler stirred aquavit cocktail. Back when I worked for the company that makes Linie aquavit, I’d often find myself in a bar that had the bottle on the shelf but no cocktails in mind for what to do with it. One of my go-tos in that situation was to order an aquavit Sazerac: same recipe as a standard Sazerac, just use aquavit instead or rye. Linie works great for this, but other barrel aged aquavits would likely do fine too. It comes out with a little less bite than a whiskey Sazerac, and a little more spice and anise. Try something like this:

2 oz Linie aquavit

1 barspoon rich simple syrup (2:1 sugar to water)

4 dashes Peychaud’s bitters

absinthe, to rinse the glass

lemon peel, for garnish

Stir the aquavit, syrup, and bitters with ice. Strain into an absinthe-rinsed glass, express the lemon peel over the drink, discard, and enjoy.